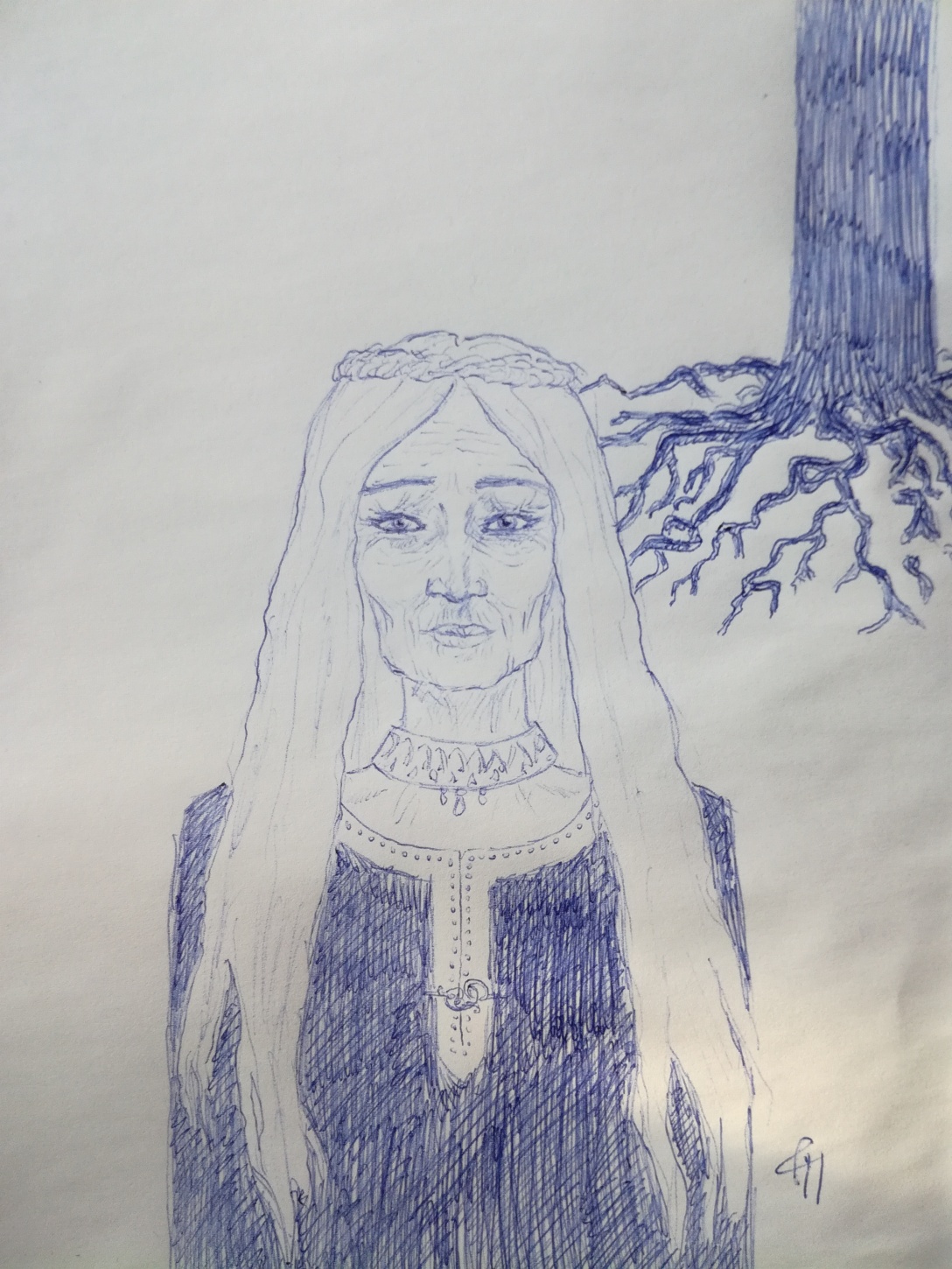

“Wisdom is counted in silver hairs” a proverb goes. “The whiter the silver, the purer the wisdom,” my grandmother would add.

Her hair was white, and she happily exaggerated her age. Many of the villagers believed her to be ancient, rumours floating around that Old Grema was a hundred and twenty years old, or even older. She had been alive since the legendary war with the Galaini, some claimed, adding that that’s why she preferred wearing her robe in the Galaini style.

Actually, my grandmother only lived to about sixty, but that was ancient enough. It’s a dangerous world. My mother gave birth to fourteen children. Only seven of us lived past the age of five, and four more were claimed by the last war. Few live to have seen several wars, or droughts, or big storms, and tell the tale. We toil all day, working the earth, which seems to drink sweat and blood as greedily as it drinks the rain.

The libraries in the capital are free and open for all, it is true, but time is a treasure the poor cannot afford. And if, like a travelling teacher once told me, knowledge is to be found in the studying of nature, then the problem remains the same. Even when we work every waking moment, we can never produce enough food to live with even a small degree of comfort, or even assurance that it will be enough to last through the winter. There are fewer mouths to feed now, but fewer workers, too. I am too weary when the dark comes in the evening, to have the will to study a flower or pursue its knowledge. I have seen my sister die in childbirth, in a pool of blood. What do I care for the shape of a golden marlip’s leaves?

No, what little wisdom I possess comes almost entirely from one source, and that source was my white-haired Old Grema. I have realized, since her death, that she was even wiser than I gave her credit for. Old Grema, you see, predicted before anybody else that the child king would grow up to be a tyrant.

“He will be known,” Old Grema would say, “as Tarim the Nalmachan. I am perfectly serious. He will be like a tree planted on a plane, with workers weeding and watering around it every day as it grows up. He will grow very tall and very large, and then, when he reaches a certain height, he will become a like the giant Nalmachans.”

At this point the story would sometimes stop, especially if it was light out, and we would gaze over to the forest. You couldn’t see it from the village, but you only needed to wander for an hour or so into the forest before you reached the Nalmachan trees. They are called Nalmachans because they are believed to have originally come from Nalmach, the empire of the giants. The Nalmachan trees, like the people they were named after, were enormous, and though they stood so far from each other you could fit entire fields between them, hardly anything grew there.

“Thirsty like a Nalmachan”, that’s another saying we have; “hungry like a Nalmachan”, too. Even if something did start to grow between the Nalmachans, like the little seedlings that cover the ground in spring, springing up from seeds brought with the wind, it soon withered and died. There was not enough nurture and water in the ground for both them and the enormous Nalmachans.

“Oh yes,” Old Grema would mutter, summoning all attention to herself again. “Believe me, King Tarim will grow tall like a Nalmachan. And do you know what we are? We are the seedlings. The King’s hunger and thirst will only grow – and we will get less and less to sustain ourselves, until finally, we will die and starve.”

If anybody except Old Grema had said it, people would have laughed, but with the widely held belief that she was well past a century old, her words carried a particular weight.

It is spring now. The first harvest is about to be reaped. In a few days time it will be ready, so we all look at the horizon anxiously. We know all too well how quickly a rainstorm can appear, and that if it does, we are better off harvesting the grain now, almost ripe but not at its ultimate point, than we are to see it all go to waste. It was bad when I was little, never a harvest that was big enough and hardly ever a time when I didn’t feel the constant, nagging pain of hunger. But now, with the raised taxes, we struggle to keep the despair at bay. We look at the horizon for rainclouds, and up the hill, for the characteristic glimpse of blue of the backbreakers’ garments. The backbreakers, that’s what they tax collectors are called now, because we have to work until we break our backs in order to produce the merciless amounts they claim. The storm on the horizon or that glimpse of blue – I dread the thought of both. They both mean nothing but despair.

For three years, we have just made it. We have gone hungry, eating every second day during some periods, but we have not starved. But I have eyes. The watchful bird sees not only the fox, but notices the change in the other birds’ song. That’s another proverb Old Grema taught me. The farm further up the hillside, where the soil has more sand – last year they couldn’t produce enough. They had to eat their seed reserve and go to a rich relative to borrow when the time came to sow. The prices were very steep, and they had to sell their land to afford it. Now it’s even worse. The taxes go up every year. And when the day comes and we can’t pay, I shudder to think what will happen.

King Tarim is only a few years older than me. When he came to power, he was only eight. His father and grandfather were bad kings too, but his great grandfather, he was one of the greatest in our history, none other than Velad Carmaltami, Velad Hawk’s Bane.

Old Grema saw King Velad several times with her own eyes and told me that he was a good king because he was a raised as a commoner. His mother was a commoner too, the woman the Old King loved but could not marry, for fear of losing a very important political alliance. It was only when the King grew ill in his older days after a battle wound refused to heal properly, that it became known that had had produced an heir: Velad.

“Velad Carmaltami was a good king,” Old Grema would say, “because he knew what life is like for us little people. But his son, and his grandson, and his great grandson? With each generation they became more removed from our reality. That’s what happens when you grow up in a palace and food is served to you on plates of gold. Each son grew up in comfort, wanting for nothing. But with the child king, ah …”

Old Grema would pause, and then say: “Peace will be his doom.”

“The peace is a blessing from the heavens!” my father would growl, always quick to get angry if someone didn’t properly honour the sacrifice of his three sons who died in battle.

“Do you have any silver hairs?” Old Grema would reply, almost lazily. She trusted in the authority her legendary age gave her. “What do you know? When I was young, I did as you are now doing, you who listen to me. I listened to those with silver hair. And I learned. I learned that times of peace are only appreciated and guarded with wisdom by those who are aware of how costly it is. A soldier who survives the war will be grateful, like you are, my son.”

My father would grunt and look away.

“But a boy who grows up in times where there is no war will be arrogant,” Old Grema said. “That’s why the peace is the King’s doom.”

She was right. Even my father acknowledges that now, now that his own hair is turning silver and the knife of time has carved deep marks in his face. King Tarim, having grown up protected and comfortable and dressed in silks, hearing of pain and war only in the shape of stories, and constantly told he was the the bravest, strongest and most honourable man in the world, only wanted more.

Old Grema said it would start with the taxes. Then revolts and rebellions will follow, and then, a shift of some sort, for better or for worse.

“There might still yet be hope, but don’t be lazy or foolish. Silver hair is a crown rarely given to the undeserving.”

I am still only a young woman, but today as I combed through my hair with my fingers, I found my first grey hair strand. I held it in my hand like a treasure, until it was caught in the wind and disappeared.

–

Short story originally published on my profile on The Prose in early 2017.